Authentic Phidippides Run: When The Run From Athens To Sparta Is Not Enough

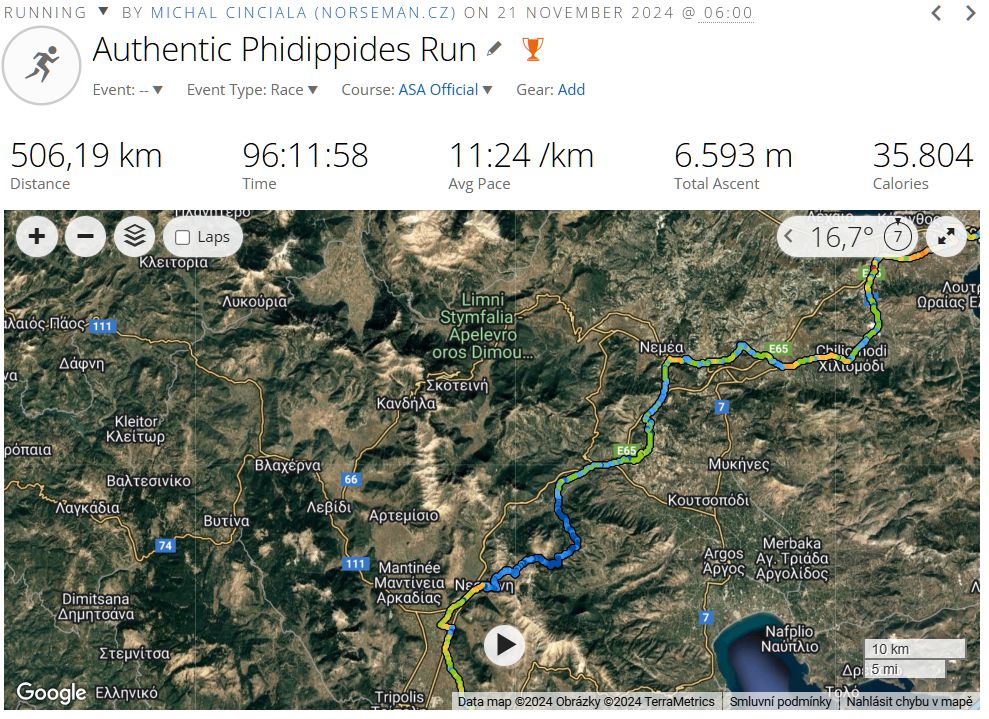

11/21/2024 – The Authentic Phidippides Run, or Spartathlon there and back, a grueling 490 kilometers from Athens to Sparta and back, retraces the steps of Pheidippides, the legendary Athenian messenger. After successfully completing the Spartathlon seven years prior, I decided to tackle this course again and, to avoid sounding shallow, double the distance.

Knowing I was far from my 2017 “peak Greek form,” and acknowledging the immutable fact of aging, I opted for a different strategy this time—one informed by my experience in two Backyard Ultra races. For those unfamiliar, this means running 6.7km at a relaxed pace each hour, walking the remaining minutes to complete the hour. I’d repeat this cycle as long as possible. This approach should yield around 100 miles, or approximately 165km, in 24 hours.

Enough strategizing; let’s get to the race.

I flew to Athens on Tuesday morning, November 19th, from Vienna. This involved a 3 AM bus from Olomouc. If you’re looking to save money on a Vienna hotel, consider a power nap on the bus! Nothing beats a late-night work email arriving in your inbox. Luckily, I had an open bottle of wine at home. I went to bed at midnight, set my alarm for 2:15 AM, and booked a taxi for 2:35 AM. The alarm ruthlessly jolted me awake, and for a moment, I was disoriented. By 2:30 AM, I was tap-dancing in front of my house, waiting for a taxi that, of course, never arrived. After five minutes, I ordered a Bolt, which picked me up a minute later. I reached the station five minutes before the bus, only to receive a message from the taxi company stating that the car was ready—haha! Of course.

I tried to sleep on the bus, but it was fruitless. I was getting nervous; after all, this was my most ambitious running project yet. This year had been more about racing than training, so I wasn’t entirely confident whether I wasn’t just going to Athens for a vacation. Unsurprisingly, I finally fell into a deep sleep about half an hour before arriving at the airport.

I traveled light, foregoing monstrous luggage in favor of a small suitcase and a backpack. I’d given considerable thought to managing my race approach and drop bags. I’d abandoned the original “punk” idea of forgoing drop bags altogether, settling on two: one for the 80km mark in Corinth (containing clothing for the first night and a spare headlamp), and one at the checkpoint 10km before Sparta (containing a power bank and warm clothing). The forecast for the first day and a half was excellent—around 17 degrees Celsius during the day and 12 degrees Celsius at night—so I planned to run lightly in shorts and a t-shirt, with arm warmers and a light jacket in my pack until Sparta. My backpack would also be minimal: in addition to the above, I carried two small power banks, a headlamp (distrusting drop bag delivery reliability), an emergency thermal blanket, and a few cables. Compared to my expectations, the checkpoints were relatively close together, averaging about 7km apart, with the longest stretch being 10km. This is why I only carried one small soft bottle.

Back to the start of my day. At the airport, I relaxed in the lounge, enjoying breakfast, coffee, and (as is customary in Vienna), strudel punctuated by beer and whiskey. Having already checked in online, I had over two hours before my flight, which I used to completely unwind. The flight itself was a blur after takeoff—the lack of sleep and alcohol consumption finally caught up with me. The post-flight mental fog persisted; first, I hunted for a ticket machine for the city center, then I struggled with the Greek display before switching to English. The whole ordeal culminated in my taking the suburban train instead of the metro, which, while passing through the center, didn’t go to my destination. So, I promptly switched to the subway in the middle of nowhere. Fortunately, the sun was shining, and the t-shirt and shorts were comfortable; I didn’t mind the half-hour wait. I got off at Monastiraki station—a place familiar from four previous visits to Athens. From there, it was just a few hundred meters to my hotel, which I reached before 3 PM.

After recovering from my twelve-hour journey, I decided not to delay. I purchased a combo ticket online for Athens’ most infamous sights and ventured into the vibrant city. Despite it being November, Monastiraki and the surrounding areas felt summery (though with more pleasant temperatures). The restaurants and market were buzzing, the atmosphere was lively. Naturally, I headed straight to the Acropolis, taking the scenic (and notoriously challenging, for me) side route over the neighboring hill. Years may have passed since my last visit, but the path was imprinted in my memory. I confidently walked past the Roman Agora, Hadrian’s Library, and up the hill.

The view of the Acropolis, bathed in sunlight, was breathtaking. I snapped a few photos, walked down the hill, and immediately entered the main entrance, passing the Theatre of Dionysus and up to the main temple. Since closing time was approaching, I limited my exploration to Acropolis and Hadrian’s Library, saving the rest for Wednesday. Fatigue was starting to set in, so I returned to the hotel to rest. Dinner and (hopefully) a few beers were all that remained on my agenda.

Wednesday, the day before the race, was hectic. I didn’t wake until before 11 AM. The race number pick-up and technical briefing were scheduled for 5 PM, so I spent the intervening hours seeing the remaining sights. Although Athens is relatively compact, covering all the sites still involved several miles of walking. I used the hour before the briefing to have lunch—Greek salad and seafood pasta, accompanied, of course, by beer and a final shot of ouzo to cap off the meal. I have to say, I was in a very good mood.

If I expected the Greek approach to such events to be similar to the Italian one, this one was even something more than that. Waiting in line for my BIB was tolerable, but the drop-bag handover was a nightmare. One person affixed a label to each bag, writing the runner’s number and checkpoint number. There were about three people in front of me, and the first guy had at least ten drop bags. After half an hour, my patience wore thin; I finally reached the front just before I exploded. I endured the first half hour of the briefing, which began an hour late, but when we heard for the twentieth time about turning here and there at places whose names were impossible to remember, and were reassured not to worry as the signage would be clear, I couldn’t take it anymore and left. It was 7 PM, my alarm was set for 4:15 AM, and I had to be at the start by 5:15 AM—no time or inclination for this nonsense. I packed my things in my room so that in the morning I only had to close my suitcase, open a beer, and watch a video. Plus, I had work to do at 8 AM—a job that was supposed to have been completed in the afternoon—which I could manage just fine. Instead of being relaxed, I was stressed, started working after 11 AM, and fell asleep after midnight. Fantastic—instead of my planned eight hours of sleep, I got four before a four-day race. I did wake up in the middle of the night because of indigestion from Greek food—which, on the plus side, saved me time I would have lost to that in the morning.

At 4:15 AM, both alarms went off. My running clothes were on the floor near the fridge. Of course, my t-shirt was completely soaked. I’d turned off the fridge in the evening, so the t-shirt had become a moisture absorber. I grabbed a spare one from my suitcase. At 4:45 AM, I locked my hotel room and headed toward the start, a little over a kilometer away through the quiet streets of Athens. Honestly, I didn’t feel comfortable or safe until getting onto the main road, where there was some traffic. With my suitcase clattering, I reached the start within twenty minutes.

Naturally, everything was still being prepared—inflating the arch and setting up electronics. I picked up my tracker. Moments later, the rest of the Czech team arrived, carrying a garish yellow vest. I refused—wearing a large Greek phi (which resembles a diamond with a diagonal line) would have felt extremely awkward. The organizers had promised to handle suitcases. To our surprise, we were the only team without support. When we asked where to leave our luggage, the organizer incomprehensibly replied, “You mean drop bags?” He only understood after we explained that we lacked support and hotel accommodations during the race, and after a brief negotiation, our luggage was transported in the main organizer’s private car. I had reservations about the pick-up, but it was still better than running 500 kilometers with a suitcase.

However, all this chaos was beneficial—it eliminated any remaining nervousness. With ten minutes to the start, I set the route on my watch. I didn’t even bother going to the restroom because of the stress—this time, I decided to combat my toilet phobia and forgo Imodium. While few things are worse than an urgent restroom break during a long race, if I needed to go, I’d just go. I would manager my gut without medication.

A live band began playing. With a minute to go, we shook hands, and I focused inward. The starting gun fired a minute late; I wasn’t surprised. The crowd roared. While we weren’t the four hundred runners of the Spartathlon, even with only sixty participants, the organizers and police provided the same level of service. We ran down the main street; police officers directed traffic at intersections, cars honked, and people at bus stops and cafes clapped and cheered. It was identical to the Spartathlon, roughly 7 kilometers to the motorway on-ramp. I felt like I did seven years ago, except I wasn’t going at the same breakneck pace. I was maintaining a 6:30 pace, at the back of the pack, and I didn’t have to push myself not to race. The fact that I had 500 kilometers left was incentive enough to be content with being one of the last runners.

It was dark, but the sky showed the first signs of dawn. When I reached the highway, I had to wait, as heavy traffic wouldn’t be stopped for just one runner. But when no one else was behind me, I crossed, assisted by the flashing blue and white beacon of a police car, like a total boss. Now, I faced one of the least enjoyable stretches—8 kilometers downhill, but in the motorway’s breakdown lane during the morning rush hour. Because the cones were spaced 100 meters apart, they provided little sense of safety, especially since roughly every third cone was knocked over by passing cars.

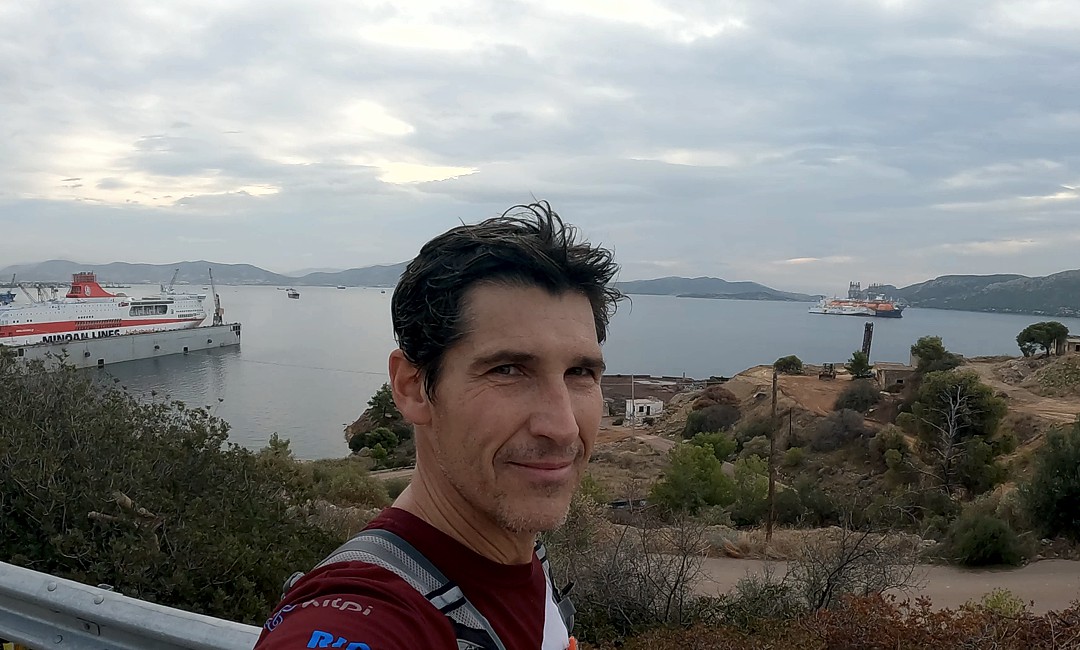

Daylight arrived. Twenty miles in, still on the highway. I temporarily abandoned my strategy, planning to resume once I escaped this inhospitable stretch. At the twenty-five-mile mark, I finally saw a sea. At the refreshment station, I filled my bottle for the first time, hit the intermediate button on my watch, and entered a more friendly part of the route. I was 45 minutes ahead of my schedule. Forty-five kilometers, a marathon in about five hours—what a sea of distance! I was running on a narrow path next to a cliff—how familiar it felt, as though I had been here yesterday.

Only during the Spartathlon does a marathon feel much longer—because of the heat and much faster pace. Now, even after nearly 50 kilometers, I felt fresh and in a good mood. I took photos of the sunken boat; it was still there. The sun was starting to break through the clouds; it was warm, but nothing unbearable. So far, I was enjoying myself relatively.

I ran along the coast. The kilometers passed slowly but surely. In the distance, the Peloponnese mountains loomed; below them, I suspected Corinth—the bread-breaking point in the Spartathlon, but in this race, a place where I could peacefully view the canal without the stress of missing a time limit. 50-kilometer mark, then 60, I hit a wall around 70 kilometers; it started to bite. I reached for guarana and took a full break—replenishing salts and food—then continued on “controlled” autopilot—functioning without fully knowing it, but remaining mentally engaged. The route before Corinth differed from the Spartathlon; I crossed the canal over a smaller bridge. It was late afternoon, slowly cooling, and darkness would arrive in an hour and a half.

After eleven hours, I reached the first major checkpoint, Examilia, where my drop bag awaited. The checkpoint was luxurious—a large house. I sat down, repacked my backpack (adding socks and Hosio pants), and prepared for the night. Breaking from habit, I removed my shoes and, determined to replenish my energy, ate a hearty bowl of noodle soup and a few cookies, along with another dose of minerals. After about twenty minutes, I decided it was time to move on. I felt good, in great shape, and positive. I was looking forward to the night—beyond Corinth, the time limits were less stringent, and the hilly terrain promised some respite from the run.

The next checkpoint was ancient Nemea, etched deeply in my memory. I’d had an emergency massage there during my first Spartathlon, barely able to walk, only to completely collapse after another marathon under Mount Artemisio. The route, however, was reversed. The Spartathlon route is runner-friendly, with rolling hills; this route involved more climbing and descending. When I saw a gas station, I couldn’t resist buying a cold beer. I didn’t drink it quickly due to prior negative experiences, but sipping a beer was a pleasant way to fill about twelve minutes of my walking portion of the hourly cycle. For the next few miles, I supplemented this with a snack from a roadside stand. Well, I was doing good at least as far as hydration was concerned.

It was pitch black, 18 degrees Celsius. The wind had completely died down. I stuck to my plan. The descent to the large checkpoint in Nemea was uneventful; I arrived after about 16 hours and 120 kilometers. I forced myself to eat—more soup and some pasta—rested briefly, and set out into the pitch-black night. Nestani was the next checkpoint, but Mount Artemisio stood in my way. Recalling the Spartathlon, I anticipated a gentle climb and descent to Nestani. How wrong I was.

It was up and down for a while; running was possible, but then it happened—a steep uphill climb. And that was just the beginning. The slope was as steep as a ski slope. Naturally, I had to adjust my strategy, content to walk the 6.7km (a yard) in an hour. I allowed myself five extra minutes, even if I didn’t meet the yard limit. My mood started to deteriorate. I was about two and a half hours ahead of schedule—not much, certainly not enough to rest.

I was exhausted. After three and a half hours climbing that relentless hill, I remembered my first Spartathlon, after which I spent ten days in the ICU. This climb offered five and a half miles and 600 meters of elevation gain. Visibility was nil; I pushed on as best I could. On the bright side, my lead on my overall time limit had increased to three and a half hours. Questions crept into my mind as to why I was doing this. The road was paved but relentlessly steep, occasionally interrupted by sections of loose rocks and dirt. I fell into step with two other runners, sharing the pain of the endless climb. I already had my jacket on; we were climbing to 1200 meters, and it was getting somewhat cold. As I started to slow, the path straightened, indicating the summit was near. The road was a bit rough, but the thrill of the descent led all three of us to run. We were still climbing a small incline when we saw a small checkpoint in the middle of nowhere. While we weren’t hungry, we all ordered hot tea with honey. I was cold, so I gratefully accepted the drink and continued. I felt sorry for the checkpoint staff, spending so much time in such an inhospitable place, not knowing that I would meet them again dozens of hours later.

The descent to Nestani was only marginally easier—a steep, winding road, with aching legs and thighs—miles of agony. Yet, Nestani remained visible below me. Fortunately, the navigational demands were minimal, as I was exhausted, and my brain was starting to fog. I knew I’d need a nap. I reached Nestani after 25.5 hours, covering 172 kilometers. The entire night had been purgatory; I was freezing. I’d been hallucinating for most of the night. I refused food, dropped my pack, stripped naked, and asked to be woken in 70 minutes.

I woke up due to my internal clock. When the woman came to wake me, I was already sitting up. I prepared my backpack, grateful for the restroom to make room in my guts for another meal—noodle soup, replenished my water supply and diluted it with orange soda. The local cola was undrinkable, both full-strength and diluted. It was very warm inside, but I suspected it would be worse outside. I got dressed and, after an hour and twenty minutes at the checkpoint, set off on my next adventure.

After resting, I had only an hour and forty minutes remaining until my self-imposed time limit, but my mood was much improved. It was cold, but after warming up, I removed my jacket. Sparta was about 65 kilometers away. I felt a little dizzy going back uphill, but I forced myself to not think about it. I found myself running alongside a Greek runner; we both followed similar strategies and frequently met up. It was pleasant, and on the way to Tegea, he shared the legend of the race. I knew the story, but I listened with interest; it helped distract from my fatigue. At the same time, I received news that unfortunately, Lenka and Zdenek, two members of the Czech team, would not finish.

I recognized the location where I’d unsuccessfully finished my third attempt at the Spartathlon in 2015. I remembered how the narrow road had been too much for me then. I was in a much better place now—not in terms of time, as I was hours slower, but in strength and determination. My fellow runner and I arrived together at Tegea, the next major checkpoint, reaching the 200-kilometer mark in 30 hours. My colleague went to sleep; I tried to eat something. I knew that from there, it was a marathon to Sparta, following the exact same route as the Spartathlon. After a short break, I resumed my run. I ran down a small road to the main road to Sparta, passed another checkpoint (run by Hungarians—who were playing Boney M very loudly, which cracked me up), and began the notorious hike up the hills above Sparta. It rained briefly, but my jacket protected me, and I knew I’d reach Sparta if nothing else went wrong. I ate, but by the time I’d finished, I looked five or six months pregnant—luckily, my jacket concealed my considerable food bulge. It seemed I would reach Sparta (and the halfway point) around 9 PM.

At the 211-kilometer mark, I suffered a severe crisis. I thought I wouldn’t make it; I wanted to lie down in the road and get run over. Fortunately, a refreshment station appeared. Upon seeing me, the woman pulled out her secret stash—offering delicious pumpkin soup, electrolytes, removed my backpack, and gave me advice. The male staff joked that she was a “Greek mom,” so I had to listen, but it was clearly half a joke. I sat down, communicating mostly with gestures (as the English wasn’t good), and felt much better; I continued, tackling the remaining kilometers. A beer I’d gratefully requested at the refreshment station proved incredibly helpful. Alternating between running and walking, I mostly kept to my strategy. I was looking for the next major checkpoint, 10 kilometers before Sparta, as it was becoming too cold, and I needed to change clothes.

A sign appeared—Sparta 33km. I didn’t know whether to be happy or angry. I walked uphill, attempted to run downhill. My right shin began to hurt—badly. I initially ignored it, but the pain worsened to the point where it was unbearable. I remembered Ultra Milano Sanremo, where I’d suffered for 100 kilometers with a similar issue. When I couldn’t endure it any longer, I took my first anti-inflammatory. It provided minimal relief. I didn’t stop at the major checkpoint before Sparta, planning to do that after the turnaround, including a full service, recharging my phone and watch, and most importantly, sleep. It was completely dark, but the lights of Sparta, visible below, helped keep me going. I descended, encountering runners heading back to Athens.

Once the road straightened, I knew Leonidas was just a few kilometers away. Arriving before 10 PM, the road traffic was minimal, but many cars still honked in greeting. It was a pleasant experience, a reward for my performance thus far. However, compared to the Spartathlon, it felt different; it was only half the race. Already in town, a Polish runner and a Brazilian caught up with me. We reached the Leonidas statue together. I maintained my distance, wanting to savor my arrival alone. The atmosphere was less frenzied than in past years, only a few people present, but the emotion remained. I hugged the statue’s leg, pausing for a few seconds, standing in the same place after so many years.

I had my photo taken. Then the rain began, so I retreated to my tent, where I gratefully devoured the offered pizza. They wanted to give me more food, but knowing I’d be eating and sleeping in a few minutes after the 10km uphill climb, I declined. The GPX route differed from the directions I’d received, but after some wandering, I found the road out of Sparta and began the uphill climb toward sleep. My leg was killing me, but I hoped it would improve after sleep. As I envied the runners heading toward Sparta, I now applauded those still en route to Leonidas. The climb went surprisingly fast. I retrieved my clothing from my drop bag, repacked my backpack, plugged my phone and watch into my power bank, headed backstage (it was nice and warm), stripped naked, and set my alarm for 90 minutes. After that, I’d only have an hour and forty minutes remaining before my time limit, but I needed to recover, particularly my sore leg.

My internal clock woke me three minutes before my alarm. I got dressed and ate properly. I felt fine; my muscles weren’t sore, and I wasn’t weak, but unfortunately, my shin remained problematic. The climb back above Sparta awaited. I couldn’t run, even if I would have avoided running up that hill anyway. The pain was so intense, that I took another anti-inflammatory. Unless I got extremely winded, the next 230 kilometers appeared to be a walking journey. I looked forward to it… sarcastically.

It was 7 AM. I had covered 283 kilometers. My leg was unchanged, a great shame, as otherwise, I was able to run normally. I tried to find the most comfortable position. The weather was awful; it was raining occasionally, and the temperature was ten degrees colder. I started walking and hallucinating when a gazebo with two benches appeared beside the road. I lay down and rested for ten minutes. As I fell asleep, the rain intensified, but I was glad the canopy protected me, and I didn’t mind the strong wind. My shorts became soaked and kept me pleasantly cool while running. I patiently waited for them to dry. I had on every piece of clothing I possessed. I was still two hours ahead of schedule, but struggling.

The three hundred-kilometer mark arrived. The sun was shining; I was at the bottom of the hill from Sparta. I smelled Tegea, another major checkpoint, in the distance. In the distance, I saw the mountains—the same ones that had tormented me on the way there. My leg felt slightly better—I’d found a position that allowed me something resembling running, in addition to walking. Any increase in speed was welcome, as it could save hours over the remaining distance. I needed that, as sleep deprivation relentlessly haunted me. Positively, my food was holding up, did not suffer from heartburn, and I had hard-boiled eggs I was gradually consuming.

Tegea—the checkpoint I needed. I was desperately needing a restroom break and notoriously reluctant to do so in the wild. I didn’t plan to sleep until Nestani, thirty kilometers away, at the foot of the mountain. When I finished, I used the facilities. I couldn’t believe what I saw—an apocalyptic scene. Apparently, the capacity was insufficient for all the runners and support staff, so the toilet was non-functional—an inch of what I suspected was a mixture of water and urine on the floor. The toilet seat was missing—at least, they had toilet paper to line the porcelain disaster. There was nothing I could do; I left a mess beyond my ability to rectify. I forced myself to forget the trauma and regained my composure. A friendly, older lady, who appeared to be of Asian descent, tried offering various things, but I only wanted beer. She looked at me, glanced meaningfully at the fridge, and produced an ice-cold beer from a hidden stash. I kept the drink for later, bid farewell, and continued on my way, into the increasingly strong wind. The beer put a smile on my face; it was 25 kilometers to Nestani, and life immediately felt a little better.

Unsurprisingly, the joy didn’t last. The wind became gale-force; I used a Ninja to cover my mouth and a Hurricane jacket.

![]()

At a small checkpoint ten kilometers from Nestani, I dropped my pack and collapsed onto the carpet for a five-minute power nap. Hallucinations were commonplace. The stretch to Nestani seemed endless; I distracted myself by looking at the mountains, which I’d never seen up close, as they were always shrouded in darkness during the Spartathlon and this race. I saw a winding road—the easier route over Mount Artemisio, which we avoided. As dusk fell, I arrived at the checkpoint, dropped everything, and took a classic race-day naked one and a half hour nap.

I woke up feeling like a beaten-down mouse. I didn’t want to leave my warm sleeping bag. But I did. I had some soup, refilled my water, and resumed my climb. I momentarily got lost—the GPS was slightly off, the markings were missing—I hesitated, my mental state limited, but I found the correct path. The good news: the descent was just as steep, but the climb was much shorter. The cold temperatures helped me warm up appropriately. I was alone—no headlamps in front of or behind me. I liked that best. My leg felt better after sleeping, and I tried to protect it. I recalled a refreshment station before the summit—the one in the middle of nowhere. I pushed forward, expecting it to appear at every turn. It didn’t. I lost track of time. Just as I thought it was canceled, it materialized. I saw a barrel fire and feared it was a hallucination—it wasn’t. I ordered tea and honey, ate something, and spoke with the two guys who’d been entertaining themselves for two days by serving runners. While they had a tent, they slept in their car (when possible) and were looking forward to returning to Athens for a shower and bed—just like me. Their shift ended sometime in the morning, unlike mine, which had another day to go.

The road ended, and a massive nine-kilometer descent began—literally. I didn’t understand how I’d climbed such a steep hill. And, to add insult to injury, my right shin began to hurt like hell again. It was generally better uphill and on flat ground, but downhill was incredibly painful. I struggled where I could have otherwise been running. I could see the town below, but it wasn’t getting much closer; the switchbacks were incredibly numerous. The checkpoint at the bottom was minimal; I only refilled my water bottle and had a meat wrap. I needed to drink plenty of fluids because my waste was turning a little brown, meaning my kidneys were suffering. On the way there, I had been running in shorts and a t-shirt; now, I was fully clothed and fuming. I must have transitioned over the mountain well, as I realized I was more than five hours ahead of schedule.

I began approaching ancient Nemea. In the hills around the highway, navigation was difficult at night. I was climbing another steep hill, hallucinating, and falling asleep while standing up. It was freezing—the frost was visible on the car windows in the town I passed. When I could go no farther, I lay down on a bench for fifteen minutes in the cold. This helped for half an hour, but after that, I used my phone to keep from falling asleep. I fell asleep while walking, and when I awoke, I was uncertain which way to go. The highway here was alternately on the left and right, and I couldn’t recall its current location. I had to check my phone to make sure I wasn’t going backward. This jolted me awake. I eventually reached Nemea, ate, but didn’t waste time on anything else.

The sun was shining, a pleasant, albeit frosty, morning.

Depending on the pace, I had approximately 24 hours until the finish, alternating between walking and zombie-like running. Slowly, the end of the Peloponnese and Corinth approached, and the faint scent of Athens started to waft in. The sun was strong enough for me to remove my jacket. I sat at a gas station, made a live video—a dog barked in the background. I had covered 406 kilometers; I felt good, anticipating what would come next. The canal was about 15 kilometers away. During the uphill climb above Corinth, I changed into shorts and a t-shirt with arm warmers; two large dogs barked furiously at me from behind a fence. After a few kilometers, however, I had to put on more layers. One of my Greek colleagues, whom I’d more or less run with for the remainder of the race, caught up with me.

Examilia—that pleasant checkpoint. I ate again, but this time, I took another 30-minute nap. Only four runners were ahead of schedule; three were currently sleeping at this point. I repacked my bag, took provisions for the journey, and had 80 kilometers remaining. Beside the highway, about ten miles before the canal, I heard soft footsteps behind me. I turned around and saw a large, beautiful dog. I was initially apprehensive, but eventually waved and invited it to join me. I had prior experience with this at the Spartathlon. The dog faithfully ran alongside me for miles, occasionally darting off to sniff trash. Before the canal, it fearlessly ran in the middle of a four-lane road, cars stopping and honking; it seemed like my dog. It’s unclear how long it would have stayed, but when the canal bridge came into view, the dog lost its nerve and wouldn’t cross. I turned to see it sadly sitting there. I waved and continued without it.

The coastal run was like rewinding the earlier leg; the kilometers crawled by, and I ran through excruciating pain. The good weather helped somewhat. Refreshments were readily available, little else to contend with—water, undrinkable sports drinks, and some small snacks. The undulating terrain didn’t help, but I persevered. The hours blended into a single, continuous moment. Darkness began to fall. Cars appeared around corners, swerving at the last second.

With my stomach tightening, I had to take a restroom break—finding a strategic spot behind some rocks. This repeated several times. I occasionally encountered my colleague; we chatted, but I preferred solitude. I passed the refinery; from the opposite direction, the destination seemed near, but it wasn’t. The marathon to the end was dark, with the lights of Athens in the distance, but my mind was failing. The pace seemed slower and slower. My leg felt as though it had been stabbed.

Thirty kilometers left. Midnight. We were in the city, but the route wasn’t direct. My colleague and I walked together, both experiencing the same leg issues. His support car assisted him; I was on my own. It was so cold that I pulled out an emergency thermal blanket and wrapped myself in it. This helped, but it was still bitterly cold. We eagerly awaited the motorway, from which it would be 15 kilometers to our destination. At every checkpoint, they congratulated me on finishing—I lost count of how many times I repeated that I hadn’t yet finished.

The motorway! Since it was around 3 AM, traffic was minimal. My colleague and I walked in the breakdown lane, taking turns hallucinating. I supposedly stopped at a tree to chat with some people; my colleague was at a bench, ostensibly at a checkpoint. His support car joined us in the breakdown lane, flashing its lights to protect us. My leg was killing me. I became so angry that I ran full speed for 300 meters, cursing, then limped for 100 meters, repeating this until the turnoff, where the final 7 kilometers were straight to the finish. My colleague kept a slow running pace, so we continued together. At the highway’s end, another car appeared—the organizers’ car—and the woman inside insisted on escorting us to the finish.

![]()

Seven kilometers would take an hour and a half in morning traffic on the main road. She turned on her hazard lights, driving a few meters behind my colleague and me. To make matters worse, four kilometers before the finish, I had to stop at a gas station for yet another poop session. The attendant, who’d just opened, stared at me like I was an alien. My Greek colleague continued; the support car waited for me. I must have looked worse…

My destination was visible a few kilometers ahead. Euphoria began to set in. I was ahead of schedule; I was going to make it. After a few more intersections, I crossed the main road and, with a triumphant feeling, reached the finish line in 96 and a half hours, greeted by the entire three-man Czech team, whose warm welcome made my return to Athens even more enjoyable. My joy wasn’t diminished by the fact that only a medal awaited at the finish line. That’s all I expected and wanted; the previous four days had more than compensated.

Authentic Phidippides Run

506 km, 96:20

20th position, 7th in category

Final word: After a long time, I demonstrated a strong spirit. It’s a great pity that a medical issue prevented me from giving a 100% performance; I lost at least five, but more likely ten hours. But the goal matters, so I have to be satisfied.

My Kilpi equipment performed excellently, as always. And thanks to H2Europe molecular hydrogen.

![]()

Užasné Míšo! Skvělý sportovní výkon a ještě lepší psaní!

Díky moc, teto. Jsem rád, že se to dalo číst.