MOAB 240: The Heat and Cold of The Utah Desert (Part 1)

Two and a half years. An incredible amount of time and water passed before I got to the start of the big race again. It took two personal challenges, which were the Kungsleden 450 and the Negev 300, before I once again immersed myself in the electrifying atmosphere of the big race.

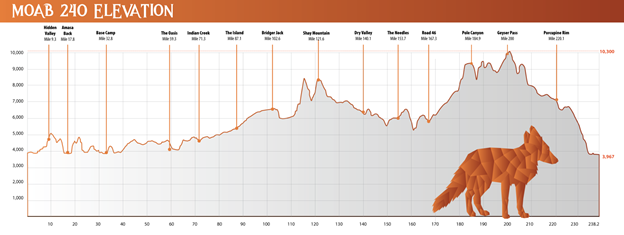

What is the Moab 240? Fully named the Moab 240 Endurance run, this race has a length of 386 kilometers and an elevation gain of approximately 9,000 metres. It offers everything from desert environments to mountain terrain to forests, all in one big circuit. Road ultramarathoners will also enjoy the course, albeit on a smaller scale, as it runs partly on gravel and tarmac roads.

I signed up for the Moab 240 under the impression of a good result and the exceptional experience of the Bigfoot 200, a last-minute replacement for the cancelled Ultra Gobi 400 adventure. I took part in with my friend Jirka Hálek and Szilvia Lubics, a Hungarian ultramarathon icon. In the interim, I had planned, and successfully completed, the 200-mile Delirious WEST in Australia, and everything was looking nicely lined up for a fall adventure in America. But what the hell, I left Australia on one of the last planes in February and then the borders closed and the world went into a Covid frenzy that didn’t allow me to “wet” my sneakers in the Utah sand until a full two years later.

I don’t know whether by coincidence or by fate, after our common Bigfoot adventure, we met again in the town of Moab with Jirka and Szilvia. After two years without any major competition, I left the Czech Republic full of uncertainty and expectations whether I was still mentally and physically up to such a challenge. I have to admit that for a long time the worm was gnawing whether I should give up, take some money back and try something else, but in the end I said to myself that who knows what will come, how much more I will be able to run, and so the decision was made to go overseas again. So how did it go?

We’re flying over the big water

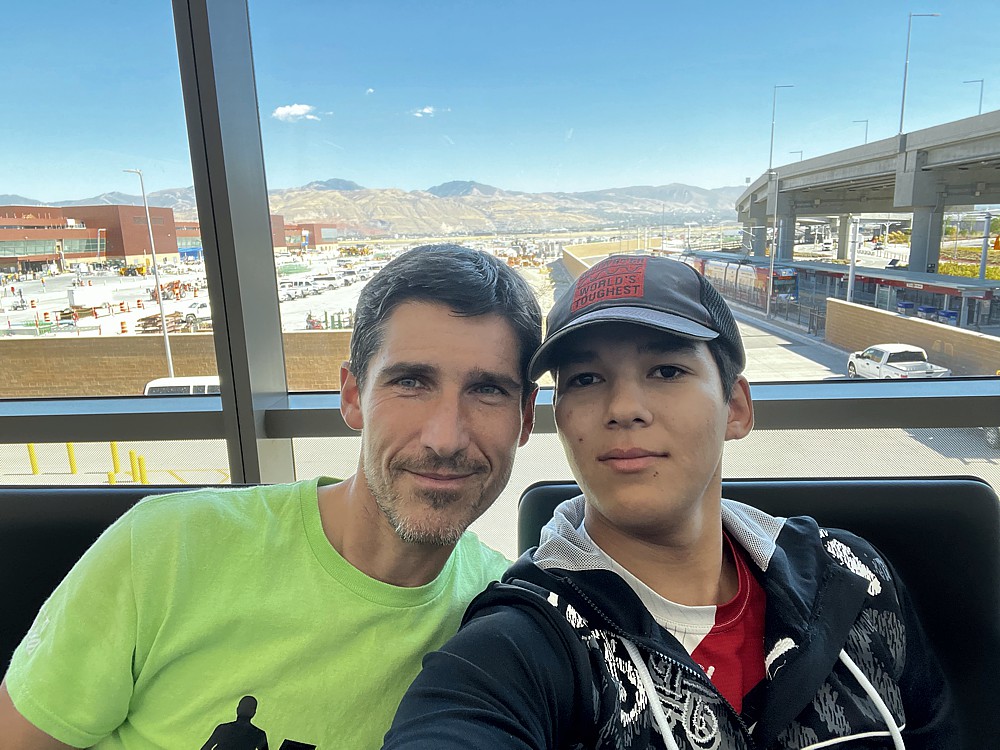

Beer at the airport. So preaches the tradition at the beginning of every event. At midnight we are at the Prague airport with my son Patrik, who will be my support for this event. The plane to Amsterdam leaves in five hours, so we have coffee at Costa’s and then two cans of Pilsner beer. Patrik should lie down on the suitcase and sleep, but instead he is playing games on his mobile phone while I finish my work duties. Well, as the classic says, “nobody gives us anything for free…”. The hours pass and faster than one would think, we pass check-in and security check and board the plane.

The pre-flight adrenaline is working, I love long flights, but at the same time I’m feeling some sleep deprivation, which isn’t the best before the race, which I estimate will take about 4 days. Plus, it’s a stomp to Amsterdam, once again having to disembark and wait for a transcontinental flight. Not surprisingly, I’m already very jetlagged and grumpy for Schiphol. Patrik is fine, the fact that his phone is still sufficiently charged keeps him in good spirits.

I skip my classic “mirudake” (just to look) errands in the airport shops, when I don’t really want to buy anything, and even though we still have plenty of time, we go to the gate and after a pre-launch visit to the toilet and a short wait, we try to board the plane. It’s not that easy, after scanning the code we are taken out of the queue, they say we have to undergo a second round of document checking to enter the US – golden Covid… But after a few minutes we do get into the cramped economy class seats and when the plane spits us out we will be in Utah.

My plan for spending half the day nonstop on the plane is always the same: keep drinking booze (since I’ve paid for the whole thing), watch some movies, eat the food they give, and eat as much of what’s offered in the back of the flight by the flight attendants that most other people have no idea about. However, plans quickly take a backseat. The plane takes off, we eat an hour later, then I watch a movie – and then 2 hours later I wake up and watch the credits, watch another movie, and 2 hours later I see more credits. And the third time, the same thing. To my credit, while I’m alive, I refill my tank with beer to feel like I’ve drunk my money.

In good spirits, and well slept, I experience the approach and landing with some trepidation. After all, I have watched dozens of hours of documentaries on air crash investigations, so every landing has something to it.

I’m a little worried about immigration too, but the initial “interview” is in the spirit of BigFoot 200. “What’s the reason for your trip?” “I’m going to a 200-mile trail running race.” The guy looks at me with an “Are you fuck.ng serious?” look, and stamps my passport. Patrik to the same, “I’m his support” – the look in the clerk’s eyes, “And you support this?”. However, the formalities are successfully completed and we have a 5-hour wait for the bus to Moab. How else, we go for a burger, which we supplement with beer from our own stock.

Five hours from noon passes quite quickly and before we know it, we’re sitting in a vehicle – but instead of a full-sized bus, we’re sitting in a van for 10 people. It occurs to me that Moab probably won’t be such a popular destination when they run vehicles like this on this line. In the rickety van, we watch our surroundings for an hour when the driver tells us that something has gone wrong and we need to change to another van at the next stop. Then, thankfully, the merciful darkness engulfs us, and we both fall into a semi-sleep, waiting for the van to eject us in Moab.

We arrive there at 9:30pm – we drive past our motel, drive, drive and drive on – whoa, about 2.5 kilometres away. We stop at a Chevron gas station and have about 40 minutes of walking with our suitcase and packs. In this godforsaken city, after 9pm, taxis are kind of “not moving”. So we pedal forward through the slowly falling asleep town, driven by the idea of a bed and an ice-cold beer, which Jirka surely has for us.

We are not disappointed. Just like in Australia, Jirka has scouted the terrain and is ready to welcome us. We chat (after all, we haven’t seen each other since Australia and it’s funny that we see each other in America, even though we’re a few hours away from each other in the Czech Republic) and go to bed after midnight. Me and Jirka as VIP (haha) on the bed (large one for two) and Patrik as support down on the floor in the sleeping bag. His consolation is that he will have the whole room to himself for at least three days of the race before he joins me as running support.

The day before the race

I wake up in the morning with a cloudy eye, to the ringing of the alarm clock and the obligatory “fuck, already?”. Patrik wakes up only when I step on him.

The schedule is pretty packed, we have to check-in, get our gear checked and we plan to meet Szilvia and her husband. We helped Szilvia with the car at BigFoot, and here she is helping us this time – it’s about 2 miles to the start, a bit of a long walk, so we gratefully take Szilvia’s husband up on his offer and get a ride in the car.

Check-in for such a big race always raises my heart rate a little. “Do I have all the mandatory gear?”, and all that. The tension is high no matter how many such races one has done. Here we go. Cell phone. Have you got the gpx uploaded? Yeah, I do. Next booth. Let’s see your gear, flashlights, etc. Okay, come in. Medical check. The doctor says, “I remember you from BigFoot and I know you from social media, how’s it going?” I’m like, “Wow, you really remember? Yeah, it’s okay, I’m not going to die.” So I got all the stamps to pick up my bib. How else do I hear, “Good luck, have a good race”.

We head back to the motel, first in a pedestrian bus with our Jirka’s American friend, who, as a previous finisher, feeds us important information, but then Szilvia and her husband pick us up at the roadside in their car, saving us all the long-distance walk to the motel.

It is late afternoon. Jirka and I go for pizza at a local Italian restaurant. The funny thing is that Patrik, who is eighteen, can’t legally have a beer, so I order two and he secretly drinks the other one.

We return to the motel and I have to decide what gear to actually bring. Because my preparation for this race can’t even be described as “punk”. I’ve thrown a diverse mix of items in my suitcase, figuring I’ll take what I think is appropriate. My two dropbags, which I turned in at check-in, included one pair of shorts, a jacket, and the other just one pair of socks. My fully packed bag, on the other hand, is about 8 kilos. I can barely zip it up. It’s a 6am start, and it’s going to be cold, so I’m going to put on my Kilpi Hurricane jacket, figuring I’ll take it off as soon as the heat hits.

Evening and early night prep is classic. I manage three beers and after Jirka and Patrik fall asleep, I meditate on what the coming hours will bring. I’m still tempted to do a fourth piece, but I resist and fall asleep around eleven (earlier than usual for me). My alarm goes off at 4:30. The “Hungarians” will take us to the start and we have arranged to leave at 5:30.

I wake up at four. Obeying my instincts, I immediately sit down on the free toilet and try to do the most important pre-start task. This is successful and I support the result with two more Imodiums. Classic, at the start and two or three days of rest and then let the will of God happen to my intestines.

No time for any pre-launch melancholy – before we know it, the car ejects us near the start, Jirka soon disappears into the crowd and I’m left alone with Patrik.

I try to punch the route into my watch, but it takes ages to load. I feel betrayed. Then the watch beeps like it’s the start of the route, but a few seconds later it beeps again like I’ve completed the whole 386km lap. It’s starting to click a bit at the back of my mind, because as always I rely on my watch completely for navigation. I try to reload the route, but in the meantime it’s three, two, one, start and run. My watch doesn’t catch up until a few kilometers in.

Starting the journey

My plan for this race is completely different from the previous ones. I intend to include little running, instead I intend to walk hard with minimal rest and sleep. A rough calculation is that this should be enough for a better time compared to my previous performances, where I physically blew off first and then finished by force of will.

The first few kilometers are on asphalt. I fail to stick to the plan and run. We leave the illuminated roads of Moab and just before we hit the ground my watch catches. Hooray! A stone falls from my heart because I won’t have to navigate by phone. The terrain is here. At the same time, dawn is breaking. It’s runnable, but I’ve got it sorted in my head and I’m off. I’ll just run downhill now and then. The fact that I’m being overtaken by a sea of people doesn’t bother me, I’ve had my experiences, we’ll see in two days, right? The downside is that my backpack is as heavy as a bag of cement. For the first (and not the last) time I berate myself for my lack of preparation. I walk through the first refreshment station. Although I don’t need it, I get a sandwich and water. We climb up the hill. Soon the sun starts to come out. The temperature goes up immediately and I start to sweat. On my left I see a city whose lights are fading as the sun rises.

I climb to what could be described as a plateau, the sun is really starting to beat down and I resist the temptation to run fast. Suddenly a valley appears, a great river. I stop and take a few video shots. I run down and after a short asphalt intermezzo, when I am running after all, I reach the Amasa Back station. The refreshments on offer are plentiful, but I settle for a sandwich and a coke and leave the station with some trepidation, as reports say there should be a swollen creek behind it, including a torn down bridge, so it’s possible I’ll get my feet wet.

You might think that’s a small, unimportant thing for an ultralight. Well, yeah, but with a race that long, it runs the risk of giving you blisters that you’d have to fight for the next 300 kilometers. Fortunately, someone has built a makeshift bridge of rocks so it’s possible to cross dry-footed.

It’s a couple of hours from the start, during which I fight the feeling that I’m not enjoying it. It’s true, the thought of another 300+ kilometers ahead of me gives me a strange feeling in my stomach. I’m trying to accept that I’m just going to suffer for a few more days.

I’m helped by the very nice views, which the desert doesn’t spare. In the middle of nowhere, there’s a break, a deep crevasse below me. Due to my ignorance, I have no idea that this is an attraction called Jacksons Ladder, a steep descent on a technical trail where every step threatens me with a nasty fall into the depths. I don’t know what’s gotten into me, but I make my way down at a high pace, stonking my way past a number of my colleagues and reveling in what a technical runner I am – the truth is, I’m not a technical runner at all, and those I’ve overtaken are even worse off.

Once I reach the bottom, I run full of enthusiasm and strength, but after a few kilometers it passes me by. I’ve just wasted my energy. At least I enjoy the sight of a factory in the middle of the desert, including a railway and rows of cars. I wonder why it’s all here.

The sun is beating down, I’m running out of water. The views are beautiful, but if you have a dry throat, you don’t appreciate it that much. I try to take a video in the late afternoon, but I can hardly get my voice out, how dry I am. I can see what the lost in the desert are experiencing. I have two deciliters of water, forbid myself even the smallest sip unless absolutely necessary, and I’m miles away from the next station. I swear loudly.

I can see the station, it seems close, but as the crow flies I can’t, so when I reach it forty minutes later as dusk falls, I’m on the verge of a dehydration collapse. Plus, after the heat of the day, I’m getting cold. The seats in the chairs by the fire are taken. I have no choice but to settle further down and knock the scythe. I get some soup and a blanket. The intensity of the coming power begins to weigh on me. I don’t linger too long, put on my headlamp and head out into the darkness.

Night and mud

At night I arrive at my first sleeping station, Indian Creek, after more than 100 kilometers. However, I don’t plan to get my first sleep until after 24 hours, so I have a burger, sit down, warm up and continue into the dark night. The wind blows here and there, it’s quite chilly.

I pedal down the road for a few kilometres. It’s a relief for me as a road ultras. I can finally turn my brain completely off. But I keep an eye on my watch, because it seems to me that the asphalt is a bit too much. Eventually, however, I do turn off the main road, first following a gravel road, which eventually becomes a full-fledged trail. And it is a trail, like a real trail. In pitch-black darkness I am gliding across the plains, crossing a few breaks, the trail is unmarked, I am orienting myself only by my watch. I see a few lights to my left, they seem to be other runners, but I can’t catch up with them. I feel very tired and at the end I realize that they are not headlamps, but stars. Oh, great. I fight the feeling that I can’t trust my navigation, and the urge to stop and wait for another runner, but by force of will I keep going.

That’s how I get through most of the night. As dawn breaks and hope comes to mind that things will get better, the trail follows the beds of dried up rivers, but they are full of mud because flash floods swept through them a few days ago, leaving mountains of red goo in their wake.

I’m trying to avoid the mud while sticking to the trail, but it’s challenging. My feelings are expressed by a large sign in the mud left by one of my faster colleagues, “Fuck mud”. By sheer force of will I manage not to get soaked in the mud and finally emerge onto the plain, with runnable terrain ahead of me. I run to clear my brain from the endless walking. I see a convenient rock ahead and find that the Imodium has stopped working and I need to empty my bowels for the first time. Just a few minutes later, a drone of filmmakers appears above me in front of The Island station. Had it arrived a little earlier, they might have got some interesting footage.

I arrive at the station in good spirits despite the all-night difficulties. I guess it’s because the sun is starting to shine, it’s warm and I can take off my clothes. I have an egg sandwich, a coke, sit for a while. My whole body aches, but I don’t admit it, because I have two or rather three more nights to go. After leaving the station I walk through the camp and in the morning everyone looks at me like I’m a moron. Frankly, I don’t care.

Shay Mountain

I arrive at Bridger Jack station. I have about 100 miles and over 30 hours in my legs. I’m not staying long. As always, I try to get an egg sandwich or a hamburger, but judging by the state of my belly fat tire, which I check regularly, it’s clear I’m not eating enough. The sun is shining, but there are black clouds near the peaks where my next steps will be taken, and it looks like all the devils are getting married there. There’s even a few thunderstorms. I veer off the trail into the terrain; it’s a creek bed, very technical; the trail periodically veers off the dry creek, but these sections are no less challenging. The trail moves between steep drop-offs, and I wait for it to head up. And indeed, the climb is extremely steep, not so much technically challenging, but I just have to pedal and not think. The serpentines wind upwards, dusk falls and it starts to get cold. When I finally reach the top, I’m going to put on some clothes, because I’m getting a solid shiver. Before the Shay Mountain station arrives, the race has one more steep climb in store for me. I’m 120 miles in and feeling pretty exhausted and sleepy, so contrary to expectations, I decide to throw my first sleep in on Shay Mountain. I’m a little confused by exhaustion, so it’s a good few minutes before I explain to the crew what I want. Eventually, however, I am directed to a tent where two runners are already sleeping.

I get a shiver. I’m sweaty after climbing up to the station, but now the damp stuff makes me cold and I’m unable to stop the shivering. I make the mistake of wrapping myself in a very coarse felt blanket instead of changing into dry clothes and lying down as I am. It’s so unyielding that the cold penetrates around the edges to my body and I am unable to warm myself. My teeth chatter loudly. I put on my headlamp and decide to change my clothes after all. Despite the unpleasant cold I manage to do so and while changing I notice that one of the sleeping runners is Jirka. Of course I don’t wake him up.

I turn off my headlamp, try to snuggle down and fall asleep. I give it half an hour, but then I wake up. For a few minutes I keep my eyes open in the dark and stare, but then with all my mental strength I force myself to get up, put on my shoes and climb out of the tent to feed myself before the next journey. Jirka is gone by then.

It seems to me that I’ve been pedalling through the night for ages, it’s completely dark, no landmark, I don’t see any other runners. At least I’m descending, and I know from the map that the next station is coming soon. I reach it before sunrise and I can’t say I’m in good shape. I’m freezing cold, I can feel something in my shoes wobbling because my feet hurt like hell, I’m sleepy and tired. I see a fire pit in front of me, beach chairs around, I take a rough felt blanket and sit down. For long minutes I am unable to move or speak, the cold air permeates all around the blanket, and I click my teeth. I don’t have the strength to eat. I just sit and stare, as if waiting for the sun to rise. After about 20 minutes, I decide that waiting is not worth it, pick myself up in the blanket, refill the liquids in the bottles and move on. I have about a half marathon ahead of me on what we would describe as a dirt road. The sun rises and, anticipating the imminent onset of heat, I retreat behind a bush, where I do a complete cleanse, including lubricating the delicate parts, changing into shorts, a short-sleeved T-shirt and putting on a cap.

At first I enjoy the journey, but as the temperature rises and later reaches unprecedented levels, my mood worsens, and once I turn onto the tarmac road leading to Dry Valley station, it’s a struggle to survive in the heat. The road is undulating, but mostly uphill. The station seems to be around every bend, but it takes its time. I stop a few times in the shade under the occasional tree. The station comes as a complete deliverance. I order a cheeseburger and a Coke and stare off into the distance to see where the three-thousand peaks are where my next steps will be.

I have 230 kilometers in my legs and haven’t slept much in 55 hours.

No doubt it’s going to be a lot of fun…

![]()